|

Last time:

To commemorate the 1761 Cambridge Patent, we circled back

four and a half centuries to the Age of Exploration centered

in 1561, then discussed the earliest American colonies.

Chapter IX:

350 Years Ago – 1661, New Netherland

Before visiting the first European culture firmly

established in New York by 1661, let’s back up to a

neighboring society also transplanted from across the seas,

which likewise affected the settlement of Cambridge. As

every schoolchild knows, 1620 was a milestone in the story

of America. Inside a cape hooking into the Atlantic, seeds

were sown for the birth of an Anglo settlement, lending the

name Mayflower, so it seems, to everybody’s family line, as

well as a line of moving vans and the Massachusetts state

flower, the ground laurel. English Separatists were bound

for Virginia but beached a bit north one dreary autumn day,

and only half of the hundred or so Pilgrims made it through

the bitter winter. With spring, though, a compact was

written, friendships were forged with the locals, corn,

cranberries and turkeys filled tummies and legendary thanks

were given to God. By 1623, Plimouth Plantation flourished

while 80 miles up the coast folks from Old Hampshire felled

trees for the British market, and likewise the next year,

1624, in later-named Maine. In 1629 five ships with several

hundred Puritans aboard anchored off what became

Salem-Beverly (including the author’s ancestor, a Richard

Raymond of Essex, a mariner and one of 30 founders of The

First Church of Salem.) By the mid-‘30s, after the Mass Bay

Colony was sanctioned by the Crown, the population center

had shifted into a harbor later called Beantown. Settlements

popped up in Connecticut (‘34) and Rhode Island (‘36) with

fleets flooding harbors, and by 1645 royal cartographers

were inking New England on their charts.

To the west 200 miles, another story emerged. Though

France had beaten the Dutch and Brits into the Owlkill

around 1540 (almost 500 years ago now), it wasn’t Paris, but

Amsterdam and London who’d forge a culture here that

displaced red man. Explorers found a land of untapped

resources and four dramatic seasons, of forested hills and

hollows, crystal clear kills and ponds. A region skirted to

the north by a long, narrow lake descending from Kanata and

on the east a wall of verdant mountains; to the south lay

the watershed of the Hoosick clan of the Mahicans, and along

the western bound a major river ran straight and deep.

Streams were found crawling with furry little critters, so

in 1614 Dutch adventurers tacked 150 miles up Hudson’s River

and built an outpost at today’s Albany, the first lasting

white presence in the region. Goods of iron and glass were

swapped with the Indians for beaver pelts; stacks of furs

became legal tender.

By 1622 Holland chartered New Netherland to the Dutch

West India Company, a venture that claimed a range from the

Fresh River (the upper Connecticut), over the Green

Mountains and into our own valley, then down to the South

River, today’s lower Delaware. Two years later New Amsterdam

was founded as the territory’s capital on Nut (Governor’s)

Island off the lower tip of the largest island of the

Manathans tribe. Other settlements sprang up, at Haarlem,

Bronck’s estate, Breuckelen. The colony was secular,

multicultural and multinational, unlike the faith-based

havens of the English also taking hold in America in the 17th

century. But ongoing bloodshed with the natives drove the

colonists in 1626 to vote a military commander, Pieter

Minuit, as leader of New Amsterdam. He planned to forge the

colony into a “new American society”, but a dream that died

with his death in a Caribbean hurricane in ‘38. Also in

1624, French Walloons, escaping religious persecution in

Belgium, sailed to New Netherland and upriver to establish a

colony near the decade old post, naming it Fort Orange for

Holland’s House of Orange. By ‘29, the Dutch West India

Company set up a larger goods exchange there, and by ‘36 one

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, a diamond merchant and founding

director of the DWIC, purchased land for himself from the

Mahicans surrounding Fort Orange, which extended a “two

day’s hike” away from and nine miles up and down both sides

of the river. Names from Holland were planted in the region

that live on today, like Tappan Zee and Rotterdam, mingled

with those of the natives like Saraghtage (Saratoga), and

later British imports, from Argyle to Williamstown.

Down-province by 1638 Willem Kieft, a Dutch lawyer,

assumed governorship of the colony, a stormy tenure rife

with conflicts with the Swedes encroaching on the South

River (near present day Philly), not to mention the Indians

around New Amsterdam, the colonists themselves and, finally,

the home country, not a healthy mix for political tenure. So

in ‘47 Pieter Stuyvesant, the original Peg-leg Pete, arrived

with legal authority from the Dutch Republic and the muscle

of a regiment of soldiers aboard four ships. Under his

leadership Manhattan and the colony of New Netherland

prospered through the 1650s. In

‘52 he changed the name of Fort Orange to the village of

Beverwyck, stripping Van Rensselaer’s private authority

(America’s first step toward creeping European socialism?)

Rensselaerwyck lay just

across the river and other Dutch settlements were founded in

the area. Three land grants were awarded by Holland: Hoosic,

Saratoga, and Walloomsac, all later honored by the English.

The story of New Netherland was artfully documented

in 1655 by jurist Adriaen Van der Donck in his

Beschreyvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant, penned in the Old

Dutch cursive (not translated into English until the 19th

century). A Description of New Netherland is

considered an early American literary classic since it’s

replete with raw details of the territory, the 17th

century American wilderness, and the tribes encountered. But

because it was authored by an arch-rival of the English, and

not in their language, for generations it lacked the cachet

of e.g. William Bradford’s Of Plimouth Plantation.

In 1661 all was well on the western front for the

Dutch, but in ’64 they were expelled by the English from New

Amsterdam without a shot fired; Holland was jammed up with

warfare in Europe and couldn’t assist in the settlement’s

defense. Richard Nicholls assumed the first governorship of

the new British Crown Province. The Dutch regained control

of New Amsterdam briefly in 1673, but the following year all

their holdings in America were ceded by treaty to England

bringing the colony under the authority of the Duke of York

and Albany, hence today’s names. Little did the Duke know

that his newly acquired island at the mouth of the Hudson

would one day become “the center of civilization”, renowned

for banking, bagels, baseball, and the bright lights of

Broadway. Up the lazy river in 1686

the newest Provincial Governor, Thomas Dongan, granted a

Royal charter to the City of Albany and assigned Pieter

Schuyler its first mayor. Since then, over 70 have served

the office, 34 of which were of Dutch decent. The fur trade

declined with fashion sense in the early 1800s, but other

area raw materials like lumber and grain amply filled the

coffers of Europe.

Over in New England, meanwhile, unrest had boiled over

between the Indians and the English that would find its way

into the Cambridge District. In 1634-38 the

Pequot War

erupted between an odd alliance of the Mass Bay/Plymouth

colonists and the Narragansett/Mohegan tribes arrayed

against the Pequots over fur trade access. The latter were

defeated in southern New England and dispersed, some

surviving for a time. In 1675

warfare broke out again, between a confederation of all

the New England Indians against the colonists, called “King

Phillips War”, a derisive name given to the major chief.

The NE Indians found friends in the French to the far north

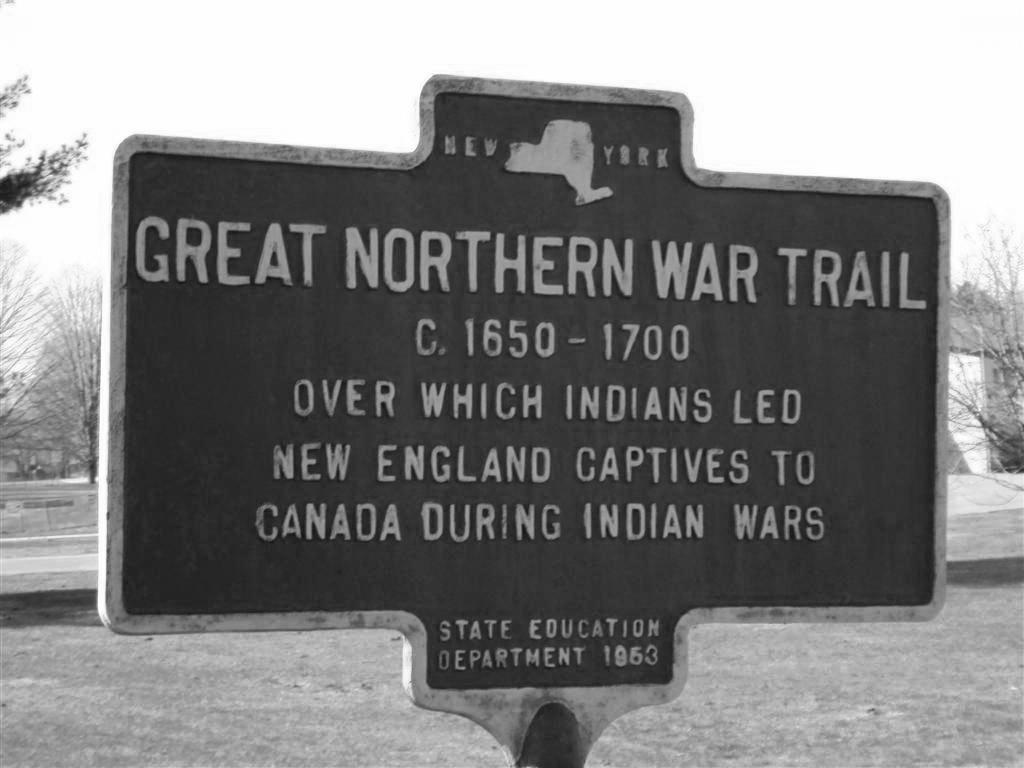

– “the enemies of my enemies are my friends” – and led

captured whites up the Great Northern War Trail (see photo).

Hundreds of settlers and thousands of Indians

perished, firearms the difference, before a treaty ended the

hostilities. By the 1680s some Pequots had

escaped over the Taconics and were camping in the White

Creek area east of Cambridge, calling their settlement

Pompanuck (corrupted into Pumpkin Hook.) Eventually the

Pequots were completely wiped out as a living, breathing

tribe. Pequot War

erupted between an odd alliance of the Mass Bay/Plymouth

colonists and the Narragansett/Mohegan tribes arrayed

against the Pequots over fur trade access. The latter were

defeated in southern New England and dispersed, some

surviving for a time. In 1675

warfare broke out again, between a confederation of all

the New England Indians against the colonists, called “King

Phillips War”, a derisive name given to the major chief.

The NE Indians found friends in the French to the far north

– “the enemies of my enemies are my friends” – and led

captured whites up the Great Northern War Trail (see photo).

Hundreds of settlers and thousands of Indians

perished, firearms the difference, before a treaty ended the

hostilities. By the 1680s some Pequots had

escaped over the Taconics and were camping in the White

Creek area east of Cambridge, calling their settlement

Pompanuck (corrupted into Pumpkin Hook.) Eventually the

Pequots were completely wiped out as a living, breathing

tribe.

300 Years Ago – 1711, The Great Awakening

As New York Province moved toward the new century,

Albany County was established in 1683 to include the Hoosic,

Owl and Batten kills, the latter known as Ondawa to the

locals. Dutchman Bartholomew Van Hogleboom had earlier

trapped the stream, known to the literate as Bart’s Kill,

then Botskill, and eventually today’s name. The 18th

century saw a new age of social and spiritual maturity

unveiled across English-America, but as the darkest hour

always precedes the dawn, in 1692 over in the Mass Bay

Colony at Salem, religious zeal overtook reason. The Witch

Trials left a trail of horror and shame (gladly for the

author’s line, Richard Raymond had relocated to Saybrook,

Connecticut Colony, by 1660.) After the turn of the

century, in 1704 the New England settlement of Hebron was

established just southeast of Hartford, which in another six

decades would birth our own valley’s Anglo population. In

1707 England, Scotland and Wales formed the United Kingdom,

an event of epic measure for the British, indeed for all of

World History, as Britannia was now set to rule the waves

and Western Civilization for 200 years.

By 1711 the census of the British colonies reached more

than 250,000, and in 1712 Albany County was parsed into

districts. The area north of Schaghticoke and east of

Saratoga appeared on the map for the first time as the

Cambridge District; the precise reason for the name here is

uncertain. Poverty in Europe and opportunity in America

packed ships leaving Portsmouth, Glasgow and Dublin,

including a lass, Sarah McConnell, one of the Cambridge

area’s oldest recorded emigrants. Born in Ireland in 1711,

she married Thomas Green in 1739, and they booked passage

and arrived in the Owlkill, where they raised three sons.

During Europe’s “Age of Enlightenment” (1700-1760),

America realized her own such period, “The Great Awakening”,

as our Founding Fathers were delivered into families of both

wealth and common standing, born to parents or raised by

mentors who ensured their education in the arts and letters.

Ben Franklin was a babe in Boston in 1706, but we know his

mark was made in Philadelphia and Paris as a preeminent

scientist and inventor, printer and postmaster, diplomat and

spy, and the eldest of the framers of our enduring national

experiment. Sam Adams followed in 1722, also in Boston, a

political philosopher and statesman of note. In 1731 George

Washington saw the light of day on February 11 (Old Style

Calendar) in Westmoreland County, VA, and became our first

great wartime general and initial Chief Exec. John Adams,

1735, was born in north Braintree (Quincy), MA. The others

followed in the ‘40s and ‘50s. As our future leaders

matured, political and religious thought evolved during the

decline of Puritan orthodoxy in America; in 1734 the Rev.

Jonathan Edwards delivered his “hellfire and damnation”

sermon, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, in

central Mass, about a hundred miles from Cambridge.

We leave this chapter in 1739 when the Walloomsac

Patent was legitimized by the Crown for Stephen Van

Rensselaer. Dutch and Walloon descendents accepted the

authority of Great Britain but the Indians were divided in

sympathies of acquiescence or resistance to the whites.

Indeed, the Canadian Francs actively enlisted the natives

to push back, and the Seven Year’s War, the French and

Indian, was just around the corner.

Next time:

Chapter X: 250 years ago, 1761, The Cambridge Patent and

the Prelude to Revolution

Sources:

The Island at the Center of the World, (R. Shorto,

2005); Old Cambridge District (A. Moscrip, 1941);

photo: Ken Gottry. (The author may be contacted at

tmraymond4@gmail.com

)

|