|

|

|

Last time: In our incremental 50-year leap back to the issuance of the Cambridge Patent of 1761, we paused a century and a half ago, in 1861, to honor the area’s heroes who fought to keep the nation whole.

Chapter VI: 200 Years Ago – 1811, The New Nation and a Second War for Independence To set the scene for Cambridge and America in 1811, a year before the new century dawned, on December 14, 1799, George Washington passed away at 68 and forever entered our hearts and history books. The Census of 1800 recorded 5.3 million citizens and 900,000 slaves, as the nation’s capital was relocated from Philadelphia to D.C. that year. On March 4, 1801, American political power transferred peacefully for the first time from one party to another: Thomas Jefferson, Democratic-Republican, was inaugurated third US President, wrestling the office from the Adams Federalists with ballots, not musket balls. In 1802, 130 miles downstate from the Cambridge District, the US Military Academy was established on the Hudson at Fortress West Point, to develop our own corps of military engineers after we had to hire Continental Europeans to design our fortifications during the Revolution. Upstate, the Great Northern Turnpike ran from Lansingburg to Buskirk’s Bridge and crossed the Hoosic with crude, uncovered bridges frequently replaced, subject as they were to flooding and ice damage. America’s first major covered bridge, built to last decades, opened in 1805 over the Schuylkill River down in Philly. The Merino sheep was introduced to the Cambridge District in 1809 and wool production became an important local industry. By 1811 the Turnpike was running through the Cambridge Valley, providing growth to the interior of Washington County. To educate the populace, the Cambridge Washington Academy was organized by 1801 and a schoolhouse built on Academy Street near West Main (chartered by NY State Regents in 1815.) A newer structure was built in 1842; readers recall a large scale model that lasted for decades on the lawn of a home at the intersection of Academy and Main.

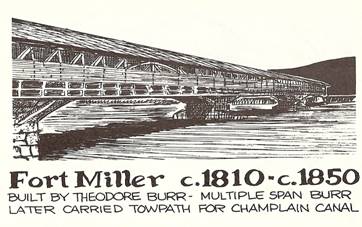

In 1802 President Jefferson and Cabinet toured the battlefields at Wallomsac and Schuylerville. Their coaches trekked up the Owl Kill Valley and the party over-nighted at Cowden’s Tavern (later the Checkered House), before passing through Cambridge. That year TJ doubled the nation’s size with his Louisiana Purchase, giving the interior States unfettered access down the Mississippi to the sea, and up the Missouri into an inviting wilderness. The Western horizon stretched the imagination, soon satisfied by Army officers Lewis and Clark. The early stages of the first American Industrial Revolution (1800-1860) forged another means beyond toll roads for commerce in upstate NY and the Cambridge Patent. In 1807 Robert Fulton gave us the first viable steamboat that carved wakes along waterways using the refined steam engine, ferrying people and goods and promoting plans for a canal system to connect the Eastern Seaboard with the Great Lakes. The Erie Canal was chartered in 1811 (construction began in ‘17) and became the original “New York State Thruway.” Passenger and freight barges were also drawn by horses and mules through several series of locks out to the western ports of Brockport, Newport, Lockport, then to Buffalo on Lake Erie. Goods were also eastbound. The Champlain Canal, running through Washington County, was on the drawing board. The earliest covered bridge in the area was constructed about 1810 over the Hudson at Fort Miller and later used by this canal system.

In March of 1809 James Madison was sworn in as our fourth President. Abe Lincoln was a month old, one of 7.2 million citizens registered in the 1810 Census, with 1.2 million slaves tallied that year. In early 1811 Madison again prohibited trade with Britain, the third time in four years. Two issues fanned new flames with Mother England, smarting still from loss of much of her Empire three decades earlier. The Crown incited Indians to harass Americans moving beyond the NW Territories around the Great Lakes, and the Royal Navy impressed into their own service England-born American sailors stopped on the high seas. “Outrageous,” clamored the U.S. press. “Untenable,” were the cries in Congress, a run-up to another war with England. But a finger was poked in the Royal eye in early 1811 as the first Americans from the East Coast arrived by ship in the Pacific Northwest – decades before tales of the Oregon Trail – to set up a fur trading colony at the mouth of the Columbia, a step ahead of the Canadians with similar designs. So who asked the Klatsops, residents there for ages? The next year, America declared war on a foreign power for the first time. Many consider the War of 1812 our Second War of Independence. The nation was struggling economically since winning her freedom, with voices on both sides of the pond suggesting collapse. But in 1813 Commodore Oliver H. Perry defeated the British a few hundred miles to the west of Cambridge on Lake Erie, a great victory for the young republic. We were appalled, though, when the Redcoats invaded Washington and burned the White House; never mind that we’d earlier torched the Canadian capital at York, Ontario. As Congress hadn’t yet authorized a new flag with 18 stars for the 18 States of the day, a 15-star banner waved over Fort McHenry in Baltimore harbor inspiring lawyer F. S. Key to pen a poem, lyrics matched ironically to an old English pub tune. This gave us our National Anthem, a hymn of reverence to the brave, the fallen (no ballad to be crooned, please, no country twang, doo-wop or bee-bop, thank you.) Britain’s resolve to win the War was worn down and a treaty was intended to end hostilities in late ‘14, but news failed to reach N’wahlans before the British were routed in early ‘15 by General Andy Jackson’s U.S. Regulars, Cajun militia, and Bayou pirates. Since Washington County had provided its fair share of troops and sailors to the War, modest lump-sum pensions were allotted to the wounded, to dependent widows, parents and children, a total of 64 from the county, 14 from the Cambridge District. Many of these events were reported in the area’s newspapers including the weekly Northern Centinel, the forbear of the Washington County Post, published in Cambridge since 1798 (not 1788, the old mast head myth.) In the local doings of the Cambridge Valley of 1811, William H. Ackley was born to Solomon and Elizabeth Ackley, third child of nine. His younger brother John (b. 1820) was the direct ancestor to Cambridge residents of today whose family name lives on in the village funeral parlor, Ackley & Ross, and Ackley Road up at the Lakes. John begat James Albert (1853), who begat Charles Henry (1893), who begat four, including Charles Albert (1917) and Francis McCabe (1920). After WWII service, Charley became one of the leading citizens of Cambridge through the second half of the 20th century, ambulance service operator, furniture store owner, funeral director, and mayor. Another Cambridge birth in 1811 was to the Reverend Philip Embury – a pioneering Methodist minister in America – and his wife Margaret, their son Peter, tenth of twelve children: “Go ye forth, be fruitful and multiply” (Gen 9:7). Today, of course, the Embury Methodist Church in Cambridge bears the name. The abundant McMorris family of the area traces an ancestor to 1811 with the birth of William, a great-uncle, son of James, an Irish emigrant, and his wife Isabella. Two deaths of note occurred locally in 1811, the first, William King, Revolutionary War veteran from the Dutchess County Militia who’d moved to Cambridge in 1792. The other was John Law of Salem, who married George Gilmore’s widow in 1790. George, another hero of Independence, lent his name to area legends and landmarks, including Gilmore Avenue in Cambridge. Cambridge High Chemistry students today have 1811 to thank for one of their rather dry lessons, as Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro published a memoir that year about the molecular content of gases. This gives our young scholars one of those concepts and constants – the Avogadro number, a scaling factor of mass per given amount of a substance (6.02214179 [30] × 1023 mol -1) either committed to memory by future chemists or looked up on a crib sheet by permission of the teacher (or not) by the rest of us. CCS Earth Science students know that as 1811 faded, in mid-December church bells along the Eastern Seaboard clanged as the New Madrid Fault erupted between Saint Louis and Memphis in one of the fiercest sets of temblors in US history: over 2000 shocks felt over several months, some 8.0 magnitude or greater, with subsidence driving the Mississippi backward on occasion! In drawing this broad chapter of the Cambridge District of 1811 to a close, five years down the road, in 1816, the Town of Cambridge divided into three townships, including Jackson north and White Creek east. That year Simon Crosby seeded a local industry that grew into the largest employer for a time in Cambridge, cultivating and packaging vegetable and flower seeds. Also in 1816 another data point was fixed for Mother Nature’s cycles and global cooling we hear so much about these days: In “The Year Without A Summer”, a volcanic eruption half way around the planet blanketed the atmosphere and, with snow falling in lower latitudes in July, crops failed and residents of Cambridge hunkered down under heavy home-made quilts for months on end. Three years later, the Panic of 1819 spread across America, the first of several economic crises of the 19th century, a predicament set off by a large debt from the War of 1812, by private western land speculation, over-investment in manufacturing, and unsecured credit and national banking politics. Sound familiar? We recovered then, only to face more cyclical recessions and depressions, like the one we’re in now, from which we’ll also recover. The engine? The Founders fashioned a Declaration and a Constitution for free men everywhere, founded on free-markets, built metaphorically like the pyramids still standing after 4000 years. Better yet, like Eisenhower’s dynamic Interstate highway system that allows unbridled movement and opportunity or, perhaps said best, Kennedy Space Port pointing mankind into the infinite. Hardly the cold, static pillars of Antiquity and Feudalism lying in fragments today, toppled by mere tremors, geologic, economic, or social. The year 1811 was a run-up to America’s first real test as a new nation. There’s no intelligent reason to fear for America’s future engineered, not by some fashionable yet transient, public-sector spread-the-wealth doctrine, but by private enterprise, long up to the task of promoting life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness through nothing less than a healthy and vibrant American Capitalism. Ask any hard working entrepreneur of the Cambridge District. Innovation and Capitalism are the children of the marriage of the Human Spirit and the American Character (with bridesmaids Wisdom and Virtue, and best man Justice, serving as watchdogs for the corruption of a Bernie Madoff.)

Next time: Chapter VII: 550 YA - 1461, The Pre-Columbian Northeast // 500 YA - 1511, First Contacts Sources include: Old Cambridge 1788-1988 (R. Clay, et al, 1988); Cambridge area historical archives; illustrations by Bob Raymond. (The author may be contacted at: tmraymond4@gmail.com)

CAMBRIDGE HISTORY LIVES © 2011 Thomas M. Raymond

|